|

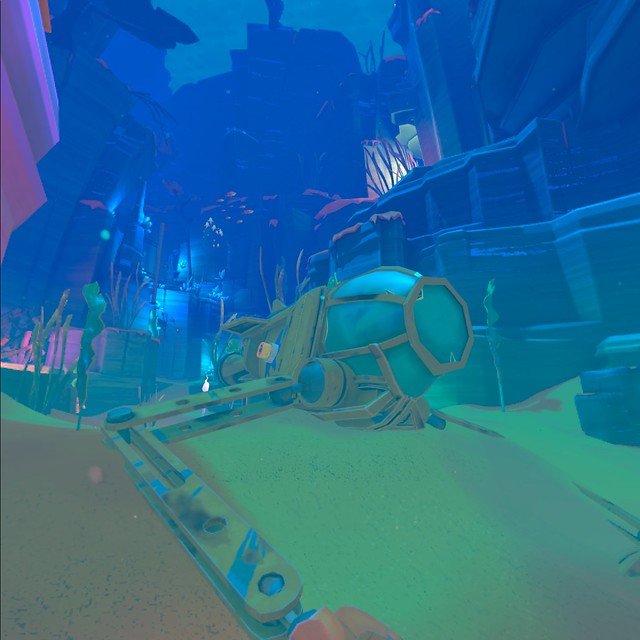

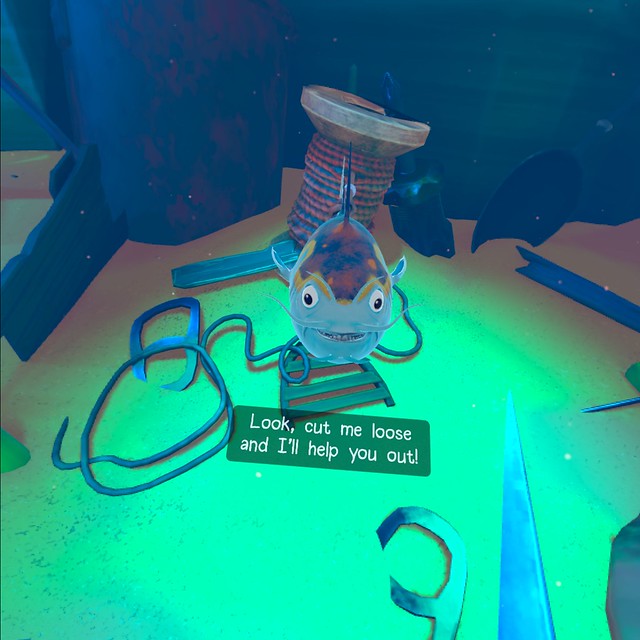

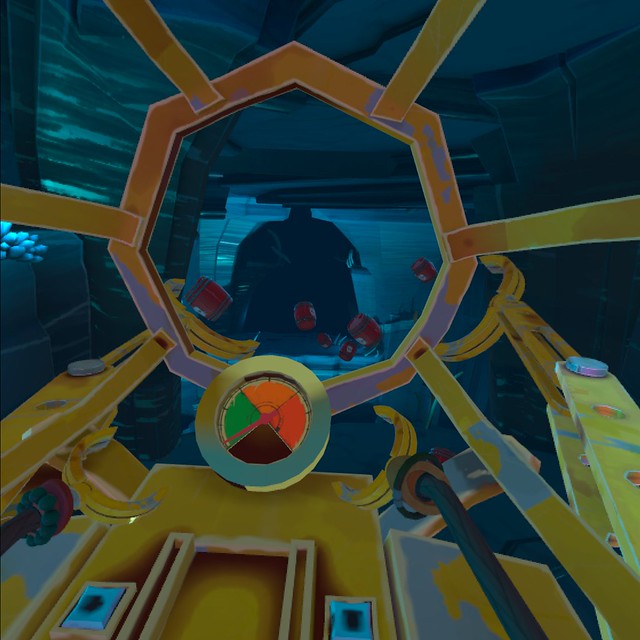

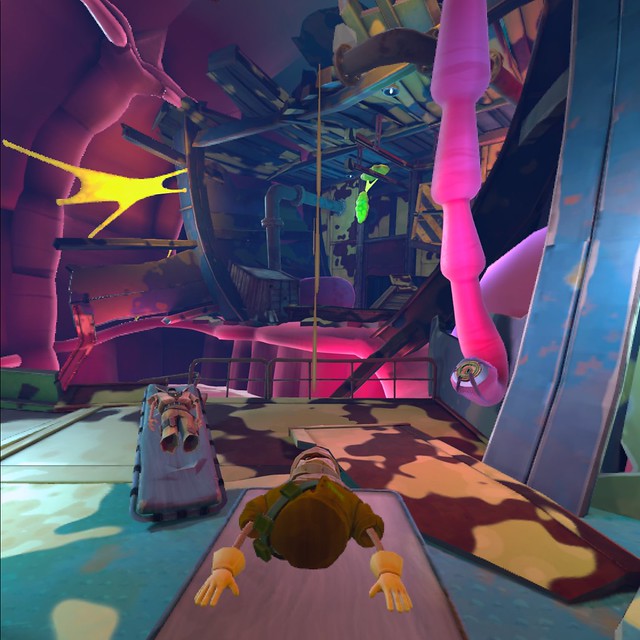

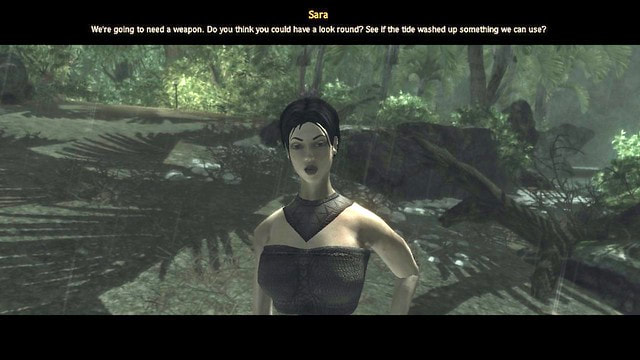

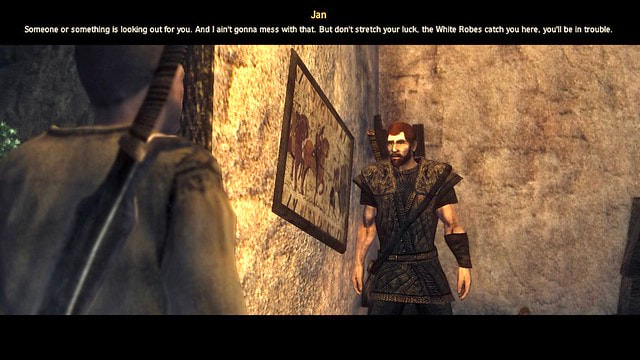

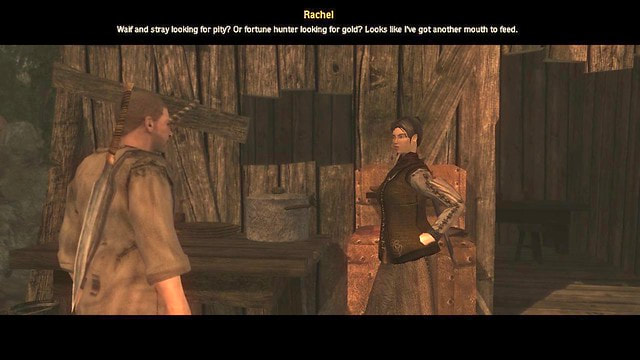

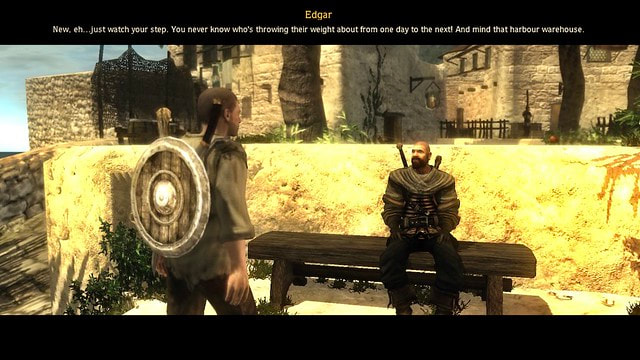

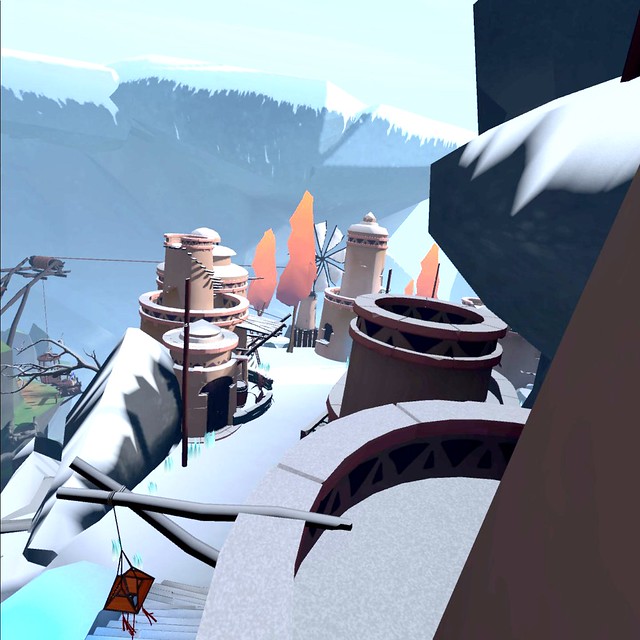

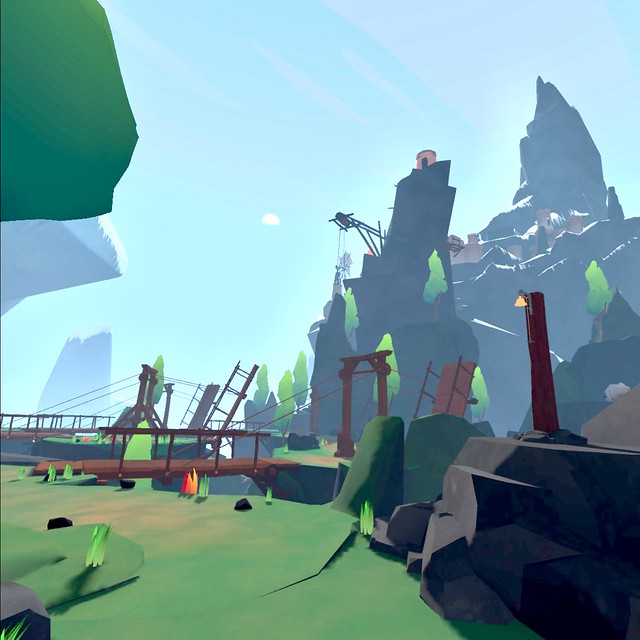

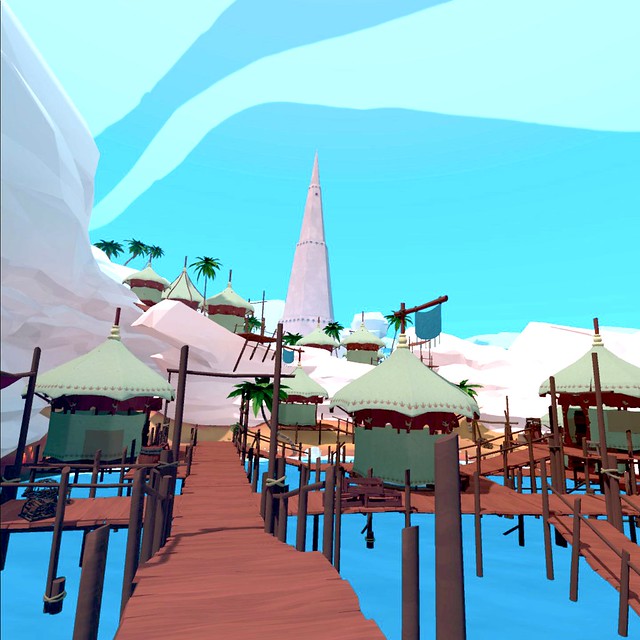

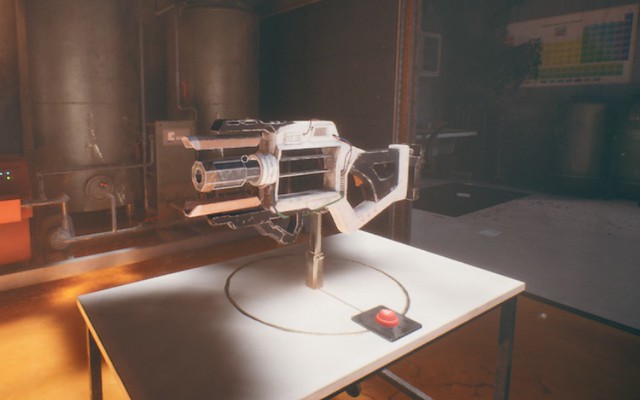

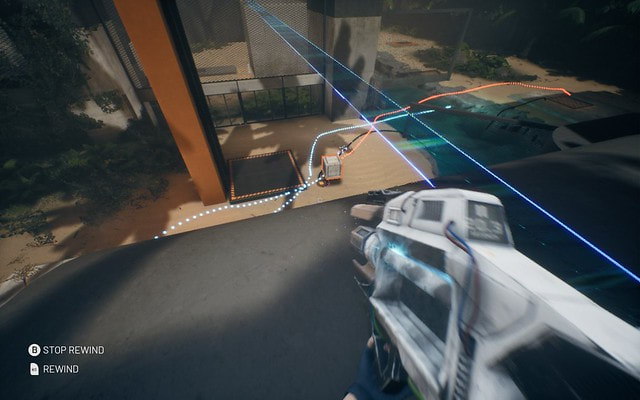

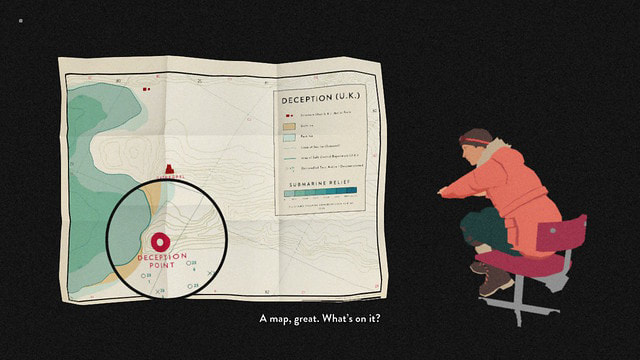

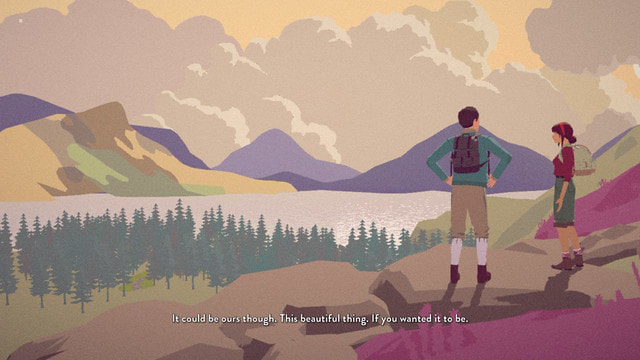

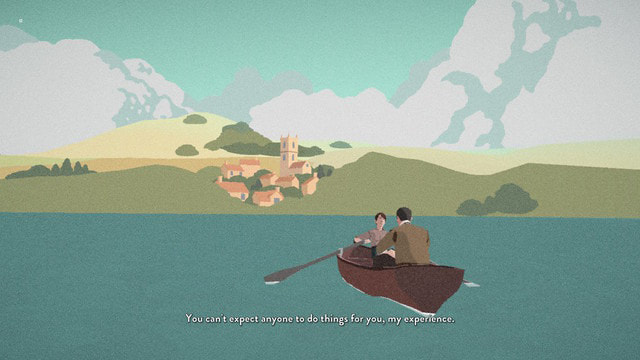

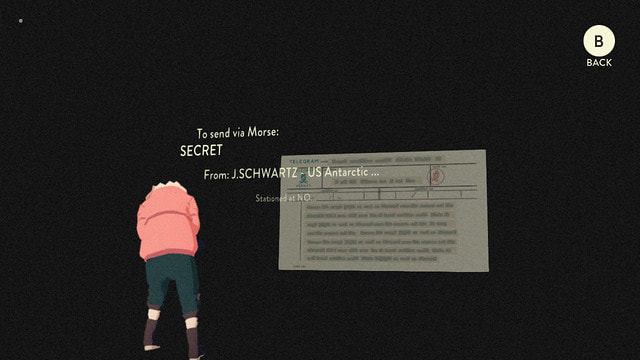

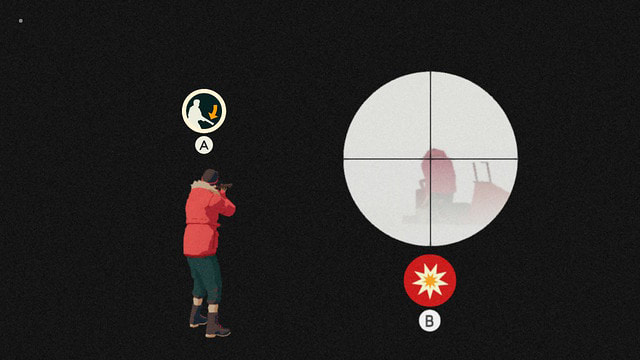

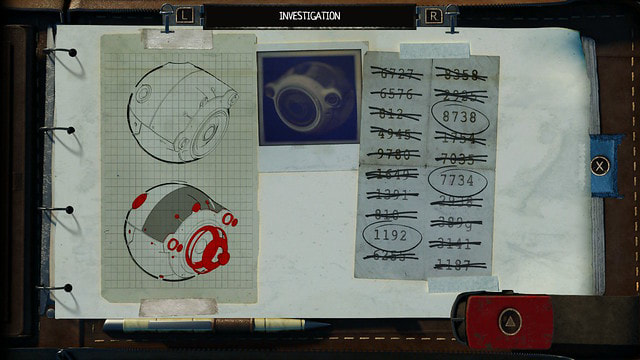

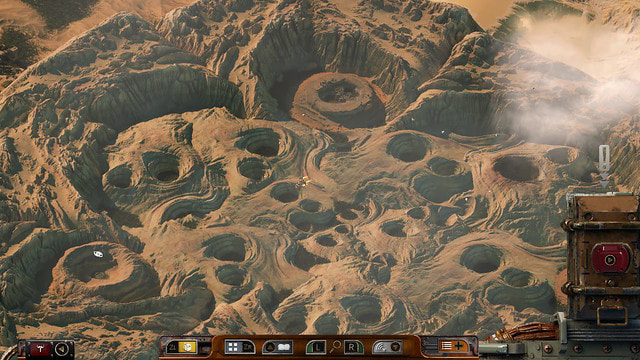

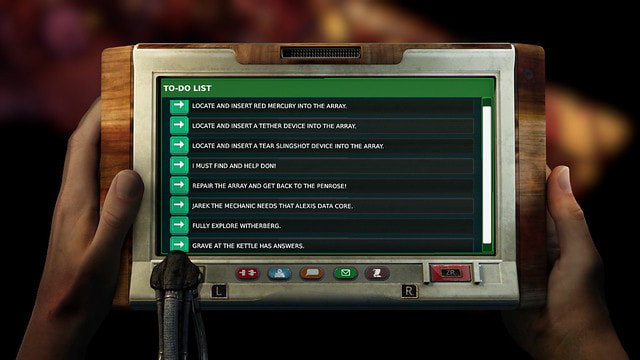

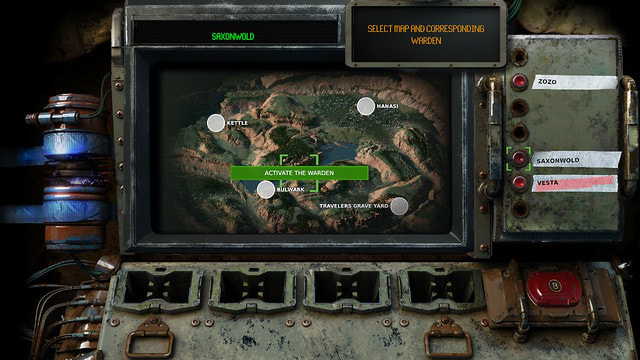

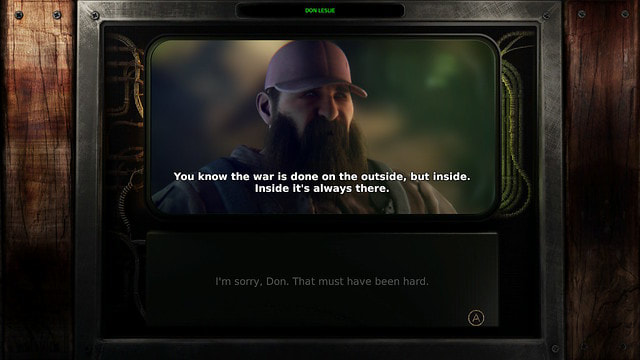

Chances are many gamers might not remember the original Outcast game that released in 1999. It was widely considered one of the early, if not first, open world RPG games. The newest title, Outcast – A New Beginning, debuted amid a historic glut of releases praised as among the best of all time. Can this relatively low-profile title defy expectations and compete in a crowded market? My interest was piqued by videos that showed off distinctive settings, jet pack navigation options, and shooter gameplay reminiscent of Just Cause or Far Cry with the challenge of taking over its lush open world one base at a time. This Outcast, as it turns out, is a deeper experience that adds jet pack actions, special abilities and a branching story enriched with strong world building. Initial impressions are a little bit of a mixed bag. The presentation is not as polished or detailed as one might expect from a modern RPG, however, inspired and beautiful art design help elevate the appearance of this alien world. Colorful, creative models for Adelpha’s flora and fauna combine with unique Talan clothing, facilities and interiors to suggest a kind of pastoral existence long attuned with this natural setting. The impressive design comes to life with myriad ambient sounds – especially the unusual calls of varied creatures in each habitat – and a Talan language that feels authentic and interesting (though just as the game picks up, English is substituted – a missed opportunity as the main character could have learned it along with the player via the latter’s use of an intuitive glossary option during dialog). Music accompanies much of one’s exploration and thankfully is a sweeping score that lends itself well to the open world and the player’s epic journey of discovery. All combined, the presentation is evocative and immersive, establishing a solid foundation from which to build this world and introduce a narrative that explores not only Talan society past and present, but the main character’s history and the threat to them both. In fact, the world building on display by developer Appeal Studios goes beyond the superficial presentation to reveal a vibrant Talan culture coming to grips with the fateful events of the first game and their newest threat of robot invaders, and how their institutions, leaders and defenders attempt to cope with these influences as well as the return of a main character, Cmdr. Cutter Slade, who may be their savior. Early on, players are introduced to Talans representing different social classes. (Spoiler alert) A Dolotai Guardian enlists Slade to help Talans despite being an outcast herself. A village chief seeks collaboration with Talan invaders to hasten their departure. And a priest helps outsider Slade in order to save children he cares for. But how the oracle Almayal is affected and their beliefs challenged is especially interesting to me. Such distinct personalities and biases influence how they behave toward Slade and other Talans. This comes into play as Slade navigates story quests or side quests, which can improve Talan trust, unite separate villages, repel invaders and reunite Slade with his family. Slade’s backstory, in fact, is slowly revealed, as is the story of alien collaborators. These different threads craft a satisfying interwoven story, at least to start with. All this brings us to the gameplay. Players begin by selecting between story, easy, normal or hard difficulties that can be changed at any time, and accessibility options in the form of vision modes and/or subtitles. Playing on the Xbox Series X initial options include right thumbstick for camera (toggle down for crouch/sneak) and left for movement (toggle down for sprint). The B button is for jumping, though another missed opportunity is grabbing ledges or climbing, which would help with navigation challenges. These standard elements also include use of the menu button to access a skill tree, inventory, database (for bestiary/characters/diaries/glossary) and settings. Soon, actions are added such as jet pack launch (A) or dodge (B), shield activation (left bumper) or attack (X), scan (down on directional pad), and shoot (right trigger), and upgrades unlocked including a jet pack double jump or glide and new or enhanced combat options. Slade can gather a variety of items from the environment, fallen foes or loot crates that can help on his journey, such as green helidium (ammo and increased weapon damage), blue helidium (jet pack upgrades), robot nano cells (combat upgrades), plants like eluee (health recovery) and creature parts. The latter two can be combined to craft potions. Collectibles like statues encourage exploration. Scanning helps identify items in the world, while enemy drops or loot crates are highlighted for easy discovery. Most of the time. One annoyance is how loot will sometimes get stuck in the environment, like a floor, making it inaccessible. You know what also gets stuck in floors? Enemies. That turns victims into amusing dolls or live foes into easy targets. Thankfully Slade has yet to get stuck. Adelpha is well designed for combat and exploration, with a variety of biomes and rock formations and an emphasis on verticality in some areas. This works for jet pack navigation but some obstacles can break fluid forward motion, such as short ledges that can’t be climbed, a finicky sprint control made worse with a slow-start animation (so players have to wait to know it works), and low ceilings that interfere with jet pack jumps off cliffs. The latter can be a problem with timed navigation challenges such as those involving shrines. One also confounded with a spirit guide that floated too far in midair until I realized that I needed to unlock other jet pack abilities. That’s fine, but it would have helped to have an alert at the start of the challenge like some games do, such as “you can’t access this,” “your skill level is too low to compete,” etc., so players don’t waste time. Despite such shortcomings, jet pack travel and the free roam nature of each setting encourage near constant movement whether surveying Talan or fighting enemies. Players will run into boundaries like fog or notifications to stay on the path/task, and even be returned to the proper location when leaping too far afield. Slade also can’t be killed when falling, as the jet pack automatically fires before touching the ground. But these guardrails don’t feel restrictive as accessible areas are expansive and allow freedom of movement to a large degree. Scaling heights or diving underwater can yield loot or collectibles such as statues, though more impressive finds in hard to reach places would encourage more investigation. Nonetheless, the terrain, Talan structures or ruins, and lifeforms are inspiration enough for me to search Adelpha high and low. The journey won’t be unimpeded as invading forces and predatory or corrupted creatures dot this alien landscape. Slade has been tasked not only with clearing out numerous bases established by the robot enemies, but with neutralizing Gork eruptions that corrupt respective locales and wildlife. His firearm will harm foes, but so can his shield when used as a melee weapon. And the jet pack allows quick movement to avoid enemy strikes. A good example of the combat is using the jet pack to surprise foes or assault others behind cover or on a platform above, approaching on foot while alternating between the shield and firearm then, when up close, using the jet pack to dodge between foes and land shield blows. The action is fast, furious and satisfying. The same tactics apply to Gork eruptions and infected creatures, but player options allow different approaches to each challenge. As with other things there are a few caveats. Namely, enemy AI is literally hit or miss. On the one hand, they fight in groups and will surround players, sometimes constantly moving and seeking cover. On the other, some foes on occasion will stand in place until killed (robot snipers in particular). If you happen to find yourself wading in water during a firefight, targeting airborne enemies can be problematic as the underwater camera perspective obscures one's view. For his part, Slade's weapon can overheat and he can be killed by enemies, but will respawn at the nearest checkpoint with full health. It's worth noting that health, shield and jet pack gauges are included in the HUD along with a minimap marked with Slade's objectives, which not only include conquering enemy bases but opening portals after earning villagers' trust (portals unlock fast travel options). Key to earning trust are side quests and conversation in the form of nested dialog trees. Overall, Outcast – A New Beginning appears to be a well crafted, open world adventure game that is entertaining to play despite occasional issues or the trope of the familiar savior come to free a hapless indigenous population. There are positive similarities to Far Cry, Just Cause and even the movie Avatar, with unique jet pack navigation options, impressive world building/design and a branching story that all help this game stand out as a title worth one's time. (This post was based on a review code of Outcast – A New Beginning for Xbox Series X/S. The game is also available on PC and PlayStation 5.) (Be sure to check out additional images here: Screenshots.)

0 Comments

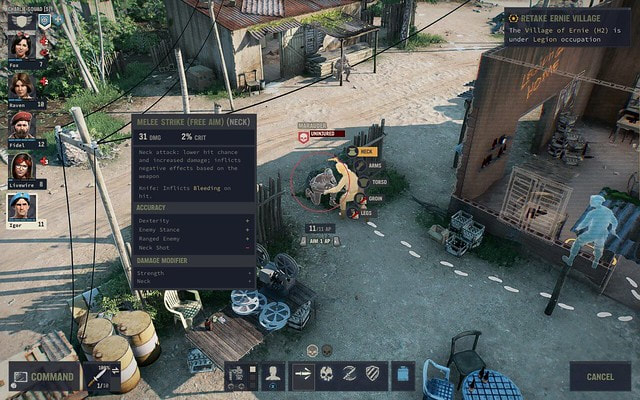

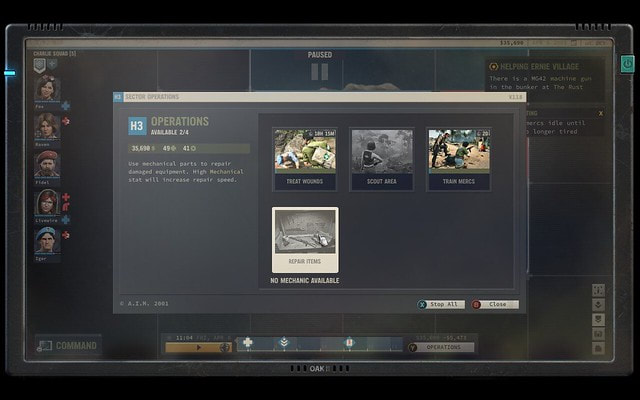

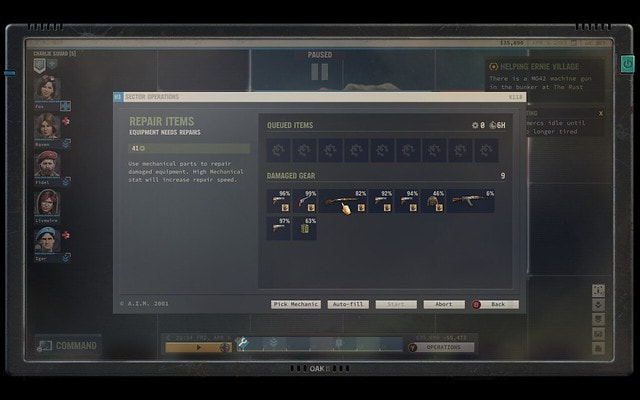

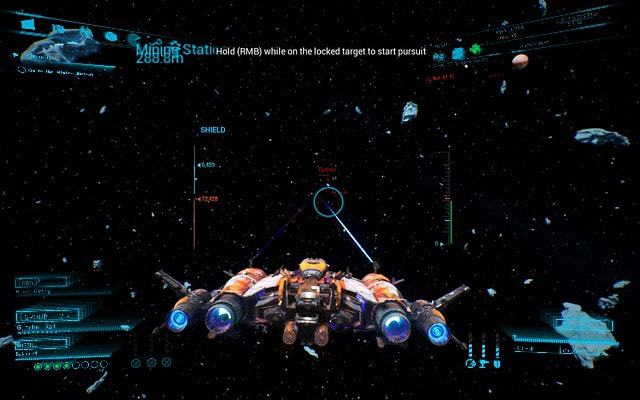

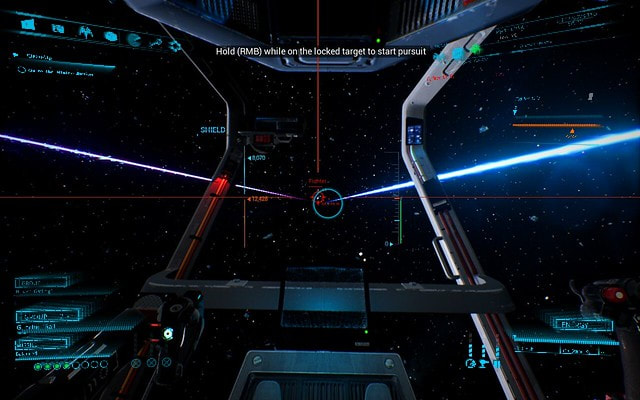

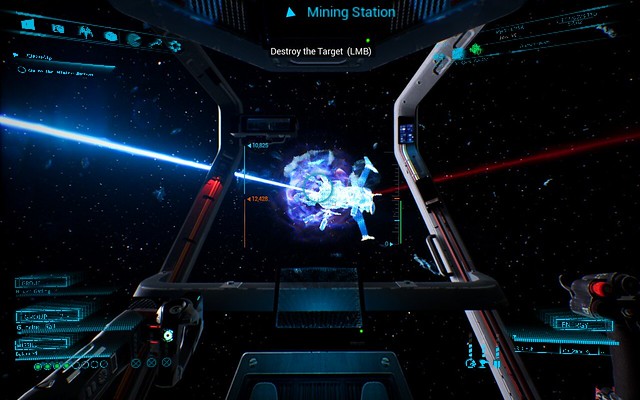

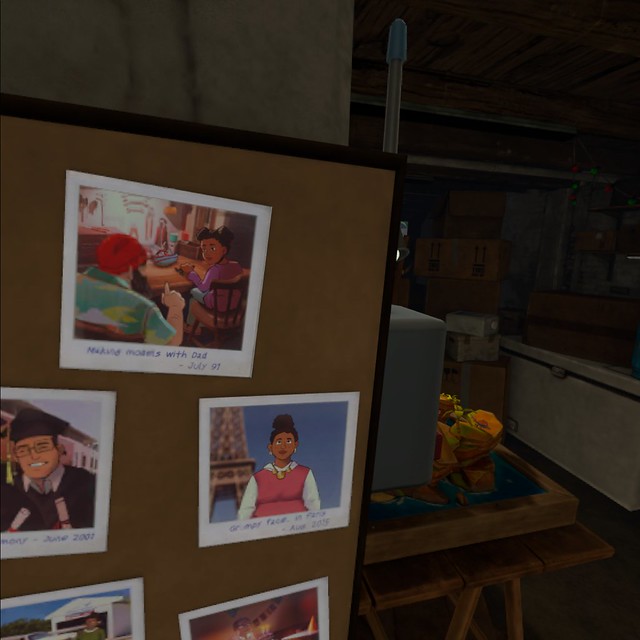

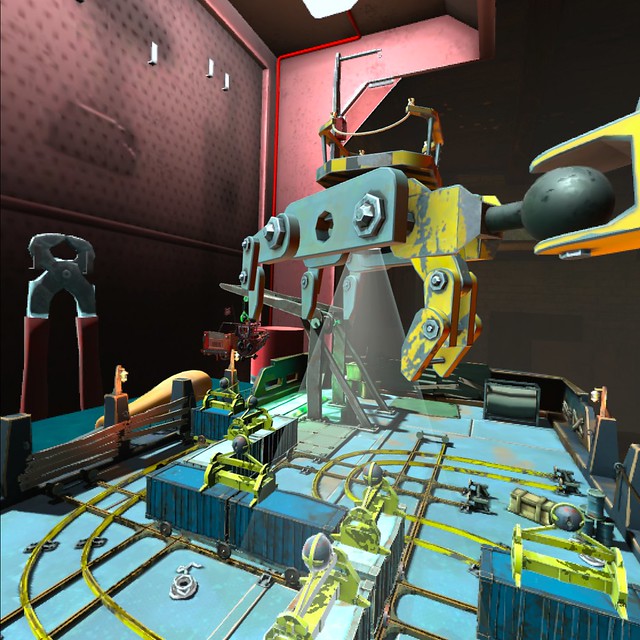

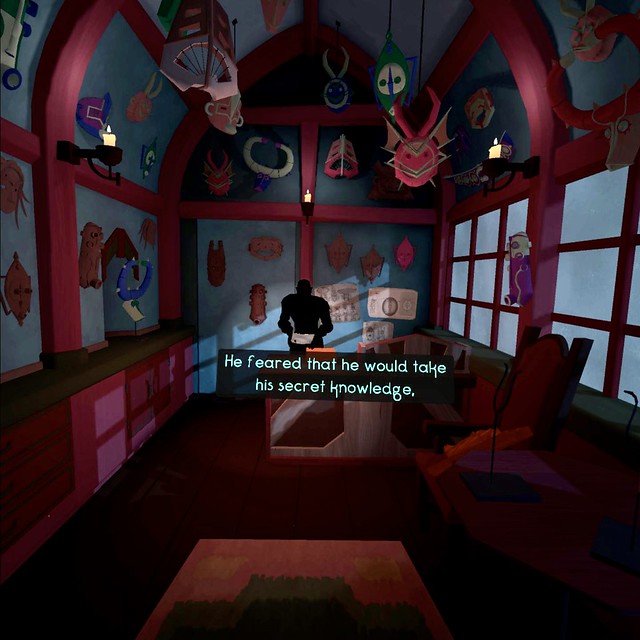

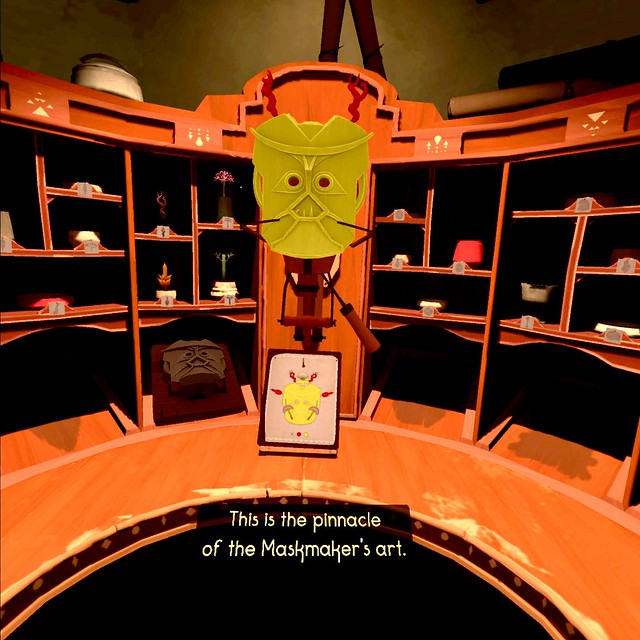

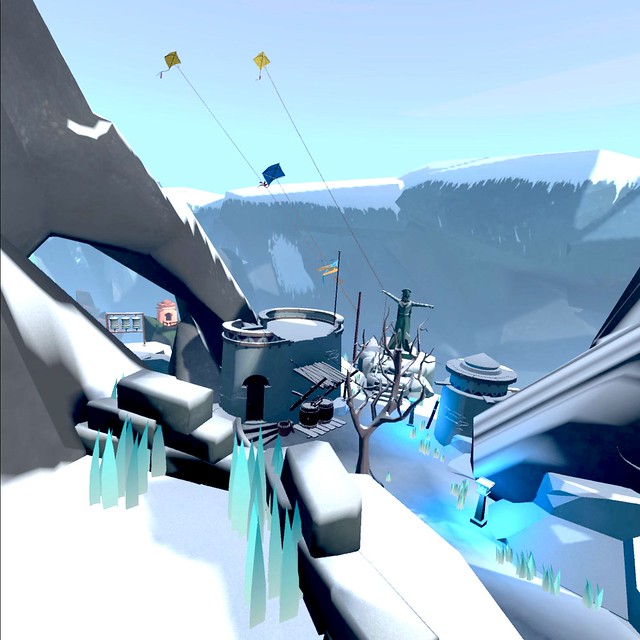

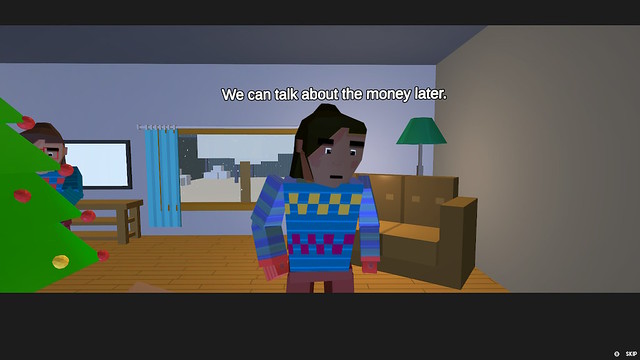

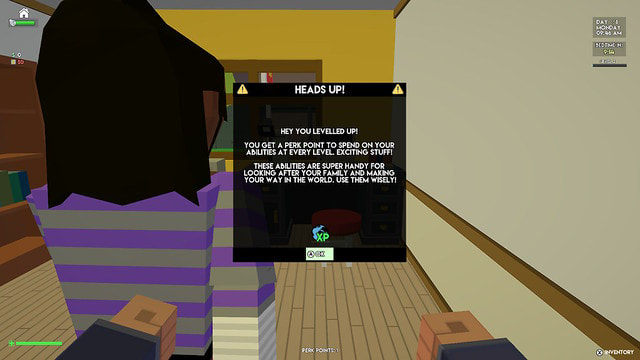

I've been a fan of isometric action RPGs since the console series Baldur's Gate Dark Alliance and Champions of Norrath, and turn-based tactical RPGs like X-COM and Divinity: Original Sin also became favorites. When Jagged Alliance 3 made news, I was eager to play a game that looked like a promising genre entry, and a solid alternative amid the Baldur's Gate 3 hype. To its credit, it's a thoughtful RPG with deep tactical roots. Developer Haemimont Games is the talent behind popular city builder franchise Tropico but is not unfamiliar with role-playing games having created the acclaimed Victor Vran action RPG. It's no surprise, then, that Jagged Alliance 3 has the appearance of a quality production with trappings of any self-respecting RPG including lots of weapons and items to loot or salvage and customization options related to character progression and crafting. But as a turn-based tactical RPG, Jagged Alliance employs a much deeper skillset that should satisfy micromanagers looking to get their hands dirty. That helps with immersion, as the story to begin with is fairly standard, though characters have personality that anchors players in the goings on. In brief, the president of Grand Chien has been abducted by The Legion in a power struggle and threatened with execution should the government intervene. That's where the player comes in. His daughter has employed the Association of International Mercenaries (AIM) to rescue him and save the country. Funded by diamond mines associated with her friend, the mercs first have to take control of them from The Legion, staff them and befriend locals to improve their output and related income via side quests including retrieving a weapon to help a village defend itself, sparing a villager's son who joined The Legion and finding a villager's husband. That's when they're not taking down outposts manned by The Legion. On Steam Deck, players will use controls including left thumbstick to select the squad, move them separately or together, and highlight objects (to move to, examine or attack); right thumbstick to control the camera (swivel or zoom in/out); L/R bumpers to cycle through squad members; and L/R direction pad to open the Action Bar (stance, sneak, single shot - free aim, mobile shot, overwatch - ambush, take cover, passive). Deep gameplay options are complemented by detailed menus that include squad selection and squad member inventory management. The latter involves menus for equipping weapons/items, exchanging items between mercs, reloading, etc., which cost points. An operations tab allows for mercs to treat wounds, train in areas such as health or marksmanship, scout areas or repair items. But such activity, which can take time, prevents mercs from being assigned other duties. As with everything else, resource management is key. Whom you hire depends on how much you have to spend, and it goes without saying that players will want to ensure they have different skillsets represented, whether that's a marksman, an explosives expert, a medic, etc. But each member likewise can be trained to improve skills in different areas so there can be some redundancy as a precaution. Notably, every action in the game costs points, even something mundane like reloading. That's where the strategy comes in, as players will have finite resources dictated by their funding and points, whether outside of the action or in it. Points will dictate whether you heal, repair, train or scout or, in combat, how far you move or how tightly you aim for greater damage. In fact, damage modifiers include increasing aim, higher ground and marksmanship skill. Other factors during combat include distance, stance, cover and which body part you target. The combat zone then becomes a chess board that demands analyzing every move and action according to a set amount of points assigned to each character. It's sometimes necessary to plan several steps ahead to anticipate possible outcomes. And even then, there's an element of chance where characters can miss their target or have little impact, opening your squad up to damaging counterattacks. It's not unfamiliar to fans of turn-based tactical RPGs, but is well executed here with deep options. As an example of the gameplay, I sent Igor to knife the last enemy who was almost dead. His attack had accuracy and damage modifiers but a lower hit chance to the neck. He missed and had insufficient points for another move, exposing him to attack. No others could help except Livewire, who I moved closer to take an aimed higher chance shot to the torso that was able to bring him down. The combination of careful tactics and an element of chance make every encounter dynamic and exciting. Speaking of, enemy AI does a good job of reacting to the player's choices. Position squad members in relative proximity to a foe, and they'll turn to face that threat. When its their turn, they'll reposition based on your team's deployment, usually behind cover but not always. Sometimes, especially on subsequent turns, they've surprised me by moving out into the open and close to my squad, then unleashing a punishing assault. It's a gamble on their part, but that's part of the element of chance. Thankfully, the controls, HUD and menus are intuitive and easy to navigate for the most part. There is a lot on screen at any one time whether during combat or in between the action. And that's be design, as there's a lot of information provided to make thoughtful choices, from attributes for potential squad members and comrades' detailed inventories to a display with their health bars and points in combat or Action Bar with options for each during their turn. And player options are not only limited to character actions in and out of combat. When speaking with the variety of NPCs encountered on the journey, the dialog tree will have an expected array of potential answers but some responses have the potential for major consequences. In one such exchange, I chose to accept diamonds from Bastien, which allowed him to leave, though is allegiance was in question. How that and other choices play out in the long term remains to be seen. Having played for several hours on the Steam Deck I'm satisfied with the deep gameplay options both during and in between the action, as well as the generally high quality presentation from the extended isometric view or zoomed in closer, and animations that are smooth and responsive as well as particle effects. Tearaway views, too, whether through trees or into buildings are effectively implemented. Furthermore, quality dialog and voice acting help distinguish characters and entertain. Issues worth mentioning are small text on the Steam Deck screen, which is not surprising considering the amount of information but at least is still legible. Also, movements with thumbsticks can be imprecise and easily overshoot an objective, not to mention that selecting a target to attack can have a small window of opportunity. To overcome these, I'm trying to customize the trackpad for movement/selection but haven't found a sweet spot yet. One other annoyance that actually lead me to reload a save file had to do with a disappearing enemy on the battlefield. During the opponent's turn, one moved behind a wall from my perspective. When I moved the camera, they weren't there. I doubted what I'd seen so moved someone to that location, only to then have the enemy reappear and kill them in point blank range. It only happened once so far but was disappointing. Overall, the deep gameplay options involved with squad management and combat create a dynamic experience with immersive interaction and thrilling encounters that's easy to recommend. The detailed and intuitive displays and menus help with decision-making, and the quality presentation only add to player immersion and enjoyment. I look forward to playing more of Jagged Alliance 3 and believe that fans of tactical turn-based RPGs will enjoy this entry in the genre. (This post was based on a review code of Jagged Alliance 3 for Steam. The game is also available on PlayStation 4, PlayStation 5, Xbox One and Xbox Series X/S.) (Be sure to check out additional images here: Screenshots.) As a fan of meaty space sojourns like Mass Effect and No Man's Sky, I was looking forward to trying SpaceBourne Part II in Early Access on Steam. Any game in EA comes with caveats for this stage of its development, and more so for the game's performance on Valve's relatively new Steam Deck platform. The fact that this massive game works on the portable is impressive, though early adopters will need to pack their patience for the trip. SpaceBourne 2 is the creation of Burak Dabak (aka DBK Games) and as such is one of the more impressive undertakings you're likely to see. The single-player, free-roam space RPG is a shooter that includes exploration, mining, trading, piracy and more. It debuted in EA on February 17 and the update 2.0 on May 24 added motherships, Nova Squad allies, a new drone management system, a new damage system and more to procedurally generated solar systems and planets with their own villages, cities, etc. Visit the Steam page to learn details about everything the game offers. To date I have spent about six and a half hours in-game, which barely scratches the surface of this deep role-playing game. That is due mainly to this game being in Early Access and not even optimized for Steam Deck. This time has been spent, as one can imagine, in training for the complex options available to the player. That it is "Playable" on the portable at this stage is quite a feat, though Valve's related claim that "All functionality is accessible when using the default controller configuration" doesn't conform with my experience. My impressions of course are based on this Early Access version so issues are to be expected, especially when considering that the developer is still working toward gamepad compatibility according to posts I'd seen (never mind Steam Deck functionality). To begin with, some text is small to read on Steam Deck and some content is off screen (I didn't find a setting to change that) including for pop up menus and buttons, restricting interaction. The game offers deep character customization, an element I always appreciate. Multiple attributes -- three each for soldier, pilot and adventurer -- affect a variety of stats that roughly boil down to damage, resistance and recharge (though adventurer has more general boosts related to experience, exploration, resource gathering, etc.). Six classes -- pirate, captain, freelancer, mercenary, explorer and merchant -- have up to four bonuses each. Preset features and custom sliders impact appearance, but options like hair color can't be selected because of a pop up that's partially off-screen. Default controls for the Steam Deck are a community configuration that uses right thumbstick or right trackpad for menu navigation; left thumbstick for locomotion (hold down for sprint) and right for camera movement; left trackpad for menu options like M (galaxy?), J (journal), T (solar system?), I (cargo) and O (character) (repeat press to return to game); X to look over left shoulder, B over right shoulder; menu/start for resume, save/load, settings etc.; holding down left trigger for zoom; top left back button for jetpack; bottom left back button to toggle first person view; top right back button to toggle the cursor. Upon starting, the first thing players will notice is the quality presentation. The detailed character model in the creation tool carries over to the game, where a multitude of NPCs linger in the initial community. All are animated though few walk about and fewer still are interactive; however, their presence and the sound of a busy street scene create an atmosphere lacking in some similar games. Some surface textures likewise are detailed and the town has a distinctive design, though the desert setting and earth tone color scheme can detract from such specifics. Of course I was initially interested in gameplay and familiarizing myself with the controls. Action starts off limited but movement is responsive and animation is fluid. The only problem I ran into early was getting stuck in between steps and a group of three people standing on them. Thankfully I figured out I had a jetpack and was able to dislodge myself. Jetpack movement itself was simple enough to execute though it took a while to figure out how to launch myself higher than inches off the ground. My first command was to find someone to speak with, which was relatively easy as an indicator showed me the direction I needed to travel in and the NPC was highlighted once in sight. However, I couldn't interact with them initially. Y was supposed to serve as the F keyboard button but didn't. I couldn't change the Y button in the settings but after changing F to LMB (which corresponds to right trigger) I was able to interact. The dialog tree had a few options though this early in the game they were not overly impactful. And besides, I wanted to hurry the story along so chose to meet with someone else who could issue me my first contract. It's interesting to note that at this stage the dialog appears to be voiced by AI, the kind you'd hear in a phone recording depending on the prompts you select (where each word is a different tone or cadence). It's a little distracting but not a big deal, and could change post-Early Access. Unfortunately during my second interaction no dialog or dialog options popped up (despite character dialog animations) and no other buttons besides camera controls worked. Locked into this conversation, I had to quit the game, but pressing the Steam button in-game crashed my Steam Deck. Once I rebooted the hardware and reloaded the game, the initial command is replayed, and I still had the same issue of no dialog or related options. I tried editing the controller layout this time (instead of just the game input settings), but still could not trigger dialog or related options. Finally, changing the control configuration to a default Steam one (Keyboard (WASD) and Mouse) worked, though it lacks many other options of course. After completing this conversation (for which the NPC voice did not sound as artificial), I had to revert to the default community control configuration to fly a ship. A few comments about the space port before I get to those controls. Here, I paid attention to shadows for the first time as spacecraft passed overhead, their respective shadows moving believably across the ground and buildings. Their sounds likewise impressed as ships landed and took off. The impressive presentation was interrupted only when I had trouble entering my ship, as my character became stuck underneath and I had to use the jetpack to break free, which sent me flying on my belly for a time. In flight, Y is held to ascend and A to descend. Flight controls proved extremely sensitive especially with thumbsticks, and I initially got caught in a barrel roll that took time to correct. In time I found that the trackpad worked best for maneuvering my craft. Unfortunately flight control configuration didn't work in every respect and I had to spend time remapping actions. Again I had to change some keyboard controls to gamepad controls (the latter still couldn't be altered in the menu). The good news is that targeting proved responsive using the trackpad and weapons appeared to work fine, though I needed practice pursuing enemy craft while firing on them. Thankfully the ship has a pursuit system, but I first had to add an extra layer of controls for ones absent from the community configuration. For instance, the ship's pursuit system was mapped to RMB, which wasn't represented in the input menu nor the configuration. I tried a few alternatives but nothing worked and in the meantime, as before, using the Steam button in game can cause a crash of the game (or Steam Deck). I left off after three crashes over six and a half hours, a lot of it spent amending the control configuration. That's not an indictment of the game at all, just the challenge of playing it on hardware it's not optimized for and with gamepad controls that are still being implemented. The HUD interface is another example, where icons and text in each corner are illegible on the Deck's small screen except for bottom right meters for health, shield, stamina, etc. Indeed, this Early Access game is by definition a work in progress. If I had a gripe, it would be with Steam's claim that "All functionality is accessible when using the default controller configuration." Considering this stage in the production process, I'm impressed with the fact that such an ambitious game is playable now on the Steam Deck and that the default community control configuration works even if considerable tweaks are necessary. If its issues on Valve's hardware can be addressed and all functionality included, SpaceBourne Part II has the potential to be a deep and satisfying adventure game on the Steam Deck. (This post was based on a review code of SpaceBourne Part II for Steam. The game is available in Early Access on that platform.) (Be sure to check out additional images here: Screenshots.) We all know how rare it is for a sequel to match the success of a celebrated predecessor – let alone exceed it – but Innerspace VR has pulled off such a feat with Another Fisherman’s Tale. The original A Fisherman’s Tale is not only a clever puzzle game but also a charming kind of fairy tale that takes players on an entertaining journey in virtual reality. It takes advantage of the medium to fully immerse players in an interactive setting that engages the heart, mind and body in equal measure. The sequel does the same while also implementing a new puzzle mechanic that entertains in its own right. This new adventure finds Nina, the daughter of Bob the Fisherman, sorting through her father’s models (and tall tales) and her memories of childhood to try and piece together the man that was her dad. It’s fitting, then, that the core gameplay is also piecing together Bob from a variety of parts after he was shipwrecked and left in pieces. When not controlling Nina, players act as a puppet of Bob to choose from various appendages that aid in solving puzzles, which might have elements such as platforming, moving parts and hidden objects for players to navigate and overcome. I’ll try to avoid significant spoilers, but if you want to experience the game for yourself, you might want to avoid some of the following detail or accompanying videos (which explore a little of the puzzle design). Bob, it turns out, can replace body parts depending on the challenge he faces. His head can be tossed for surveying/scouting, his hands for grabbing/retrieving, a claw for cutting and a hook for grappling, not to mention a fish tail used for swimming. Sometimes a puzzle will require several, and at times in combination. That will depend on the level design and puzzle elements. Each level is an interactive model where the action takes place, from an island to a ship to a freight yard and more. Free movement and teleportation are the default locomotion options to navigate each area, which are designed with scale and verticality in mind to encourage consideration of all the tools at the player’s disposal. A typical puzzle might involve Bob launching his head to survey inaccessible areas or just get a new perspective, using the hook to grapple beyond an obstacle, employing the claw to cut a rope and utilizing a hand to pull a lever, turn a crank or retrieve an object. It's important to note that Innerspace VR puzzles are anything but typical. While they might involve familiar objectives such as fetch quests or navigation challenges, they take advantage of changing perspectives in virtual reality for a unique twist. An example is when using Bob's detachable head to also control his body or appendages, but later, more surreal levels use elements like scale (as in the first game) to inspire creative solutions. Gameplay controls on the Meta Quest 2 include using triggers to launch a hand, claw, hook, etc.; grip buttons to retrieve a hand, etc.; B+Y buttons to launch or retrieve Bob’s head; and thumb sticks to orient and move a launched hand, etc. All controls work well and are fairly intuitive, though it’s to be expected that some movements take practice when changing perspective, such as controlling Bob’s body when watching it from his launched head, or when moving a launched hand. In total, the puzzles are thoughtful without frustrating, and often entertaining. The only issues I encountered playing the game should not prevent players from enjoying it overall. In general, you can’t do things the game doesn’t want you to, even if it seems like you should be able to, i.e. teleport to any surface that appears accessible or launch an appendage anywhere you want (you can point your hand etc. but it will launch in the direction of specific spots, which can annoy when engaged in trial and error puzzle solving). On one puzzle, a key object would disappear and rematerialize – not where it originated, but in another spot out of view; I had to restart before I figured out where it went. The otherwise solid controls, well-conceived levels and creative puzzles are complemented by an impressive production that meets the high bar of its predecessor. Settings are beautiful with simple lines but inspired details and a rich color palette. The story is entertaining and poignant, and the dialog is engaging and thoughtful. The music and voice acting evoke fairy tale charm with a lyrical score and endearing, earnest delivery. Each element contributes to an overall enchanting tale that is superb in its own right but succeeds especially as the perfect bookend to the terrific game that came before. Innerspace VR (and publisher Vertigo Games) knows what works in a virtual reality space. Their games take advantage of the medium to deliver immersive experiences that engage players completely, from fully interactive gameplay to charming stories with emotional hooks. Another Fisherman’s Tale successfully introduces a new gameplay mechanic and an extension of its story to deliver a perfect sequel that might the high expectations established by its predecessor. It’s a rare feat for virtual reality let along video games in general. (This post was based on a review code of Another Fisherman’s Tale for Meta Quest 2. The virtual reality game released May 11 on that platform as well as on PSVR2 and all PCVR platforms.) (Be sure to check out additional images here: Screenshots.) I've always wanted to play PC games like Risen or Gothic but never had an opportunity until I obtained a Steam Deck. However, as with many games, controller configurations aren't always readily available for Valve's portable device. And despite an impressive customization tool, creating one from mouse and keyboard controls can be challenging. So when THQ Nordic announced it was re-releasing Piranha Bytes' game Risen with gamepad controls and an updated user interface, I was interested in exploring what made this older RPG such a well-known title. Knowing the game wasn't remade or remastered, I went into the journey with lower expectations than I would for a newer production. But despite aged design, it's an enjoyable trek. Thus far I've spent over eight hours wandering the island of Faranga as a survivor of a shipwreck. I've explored beaches, swamps, rolling hills and caves, and visited settlements including a bandit camp, town and farmland in between. The island is not huge but it does pack a lot into each area, mostly within settlements where NPCs and related quests appear. One standout for me is how the various quests are interwoven among NPCs and factions. For instance, in the bandit camp, people need to be fed, protection money paid, predators dispatched and work completed, among other tasks. These are interdependent so some can't be completed if others are left undone. This isn't a new concept, but too many RPGs rely on independent quests that sacrifice the big picture. It helps that each character appears to have a distinct personality and quality voice acting helps distinguish them. Grievances -- sometimes petty -- are aired and at times compel the player to take sides, a circumstance that becomes more common and stark as the game progresses. In particular, choices and quests in town often favor the bandits/townspeople or the strict Inquisition. The reason boils down to the story of how temple ruins on the island were unearthed and residents coveted reported riches inside. The Inquisition came to the island's shores with their own designs on the ruins and sought to establish order from their Monastery, pitting Inquisitors and allies against townspeople including bandits. Complicating matters are the creatures that emerged with the ruins. It's a simple premise that provides a solid foundation for the central conflict of Risen as well as for the context for the game's quests and player choice. Certain decisions have more impact than others, such as those that align with a certain faction. And the tasks themselves can range from simple fetch quests or combat to attempting to convince someone to take a stand, act or make a decision. This is where gamepad controls come into play. On Nintendo Switch Joy-Cons, left shoulder button draws melee weapons while right draws ranged weapons (bow or crossbow). In combat, melee weapons correspond to face buttons: A results in different strikes, B blocks and X evades. Ranged weapons are fired with the right trigger. Left thumb stick moves, right controls the camera (pressing down jumps). The directional pad pulls up different menu screens. Up is for inventory, down are maps, right are skills and character stats, left are quests and related maps as well as where to find trainers. Navigation within each menu screen is managed with shoulder or trigger buttons and/or thumb sticks. Plus button has game options and settings, minus button controls zoom. One function I didn't explore until recently is hotkeys. Highlighting various consumables or spells, pressing the left trigger then selecting a face button or direction on the respective pad will map the item to that hotkey. Pressing the left trigger at any time plus hotkey will consume the respective item or cast the assigned spell. The gamepad controls are surprisingly intuitive overall for both menu navigation (as described above) and combat. Drawing or sheathing weapons is quick and easy, melee combat early on involves simple strikes and defensive postures and ranged attacks are a little more nuanced as distance is a factor. As in most cases, combat boils down to timing and pattern recognition. The only drawbacks to combat that I've found during my gameplay thus far involve melee strikes and blocking. Two or three strikes in a row will result in different attacks. But stringing them together leaves players open to attack as enemies can reposition in between attack animations. Similarly, blocking appears to initiate a target lock, but it sometimes breaks and leaves players vulnerable. Injury or death due to these factors can be annoying, but I take the good with the bad. These scenarios are also examples of good enemy AI that will constantly evade or flank players, meaning players have to keep on their toes and switch up tactics on the fly. Some games do this well, but too many disregard this. Speaking of AI, one's allies also demonstrate quality behavior. If you engage with enemies near bandits or guards (or if you're like me and intentionally bring foes back to armed characters/NPCs for an added assist), they will arm themselves and defend against the common enemy. The downside is that they could die -- one character, for instance, did perish fighting a bog body beside me. Not sure how that impacted their influence though my character did report their death. Similarly, I was impressed with how NPCs react to my character. If I enter someone's home, they will immediately follow and warn me to behave. Or if I draw a weapon around bandits/guards, they will arm themselves and warn me to sheath said weapon or attack if I don't. Strike one by accident during combat, and they'll strike you down (not dead, thankfully). Once again, too many games pay little to no attention to these details, so it's a welcome development (no pun intended). As for enemies, there is a decent variety early on, including grave moths, stingrats, ogres, skeletons, wolves, bog bodies and variations thereof. I also faced off with some spellcasting creature in a mine. Both the ogre and that creature pretty much finished me off with one hit. But it's nice to play a game where foes don't scale to your character and you learn to pick your fights. Returning to a fight when your character has leveled up and/or procured better weaponry or spells helps when there is a process that supports it and Risen does enable players to train and grow various skills and purchase or trade for better weapons or spells. It helps that the quest menu identifies whom players can train with for a price. Despite being a port of an old RPG, this game earns its renown for good reason. The characters, quests and enemy or ally AI all contribute to an engaging experience thus far, and the added gamepad controls and updated UI do a good job of upgrading the experience for more modern consoles. Of course the presentation is dated, but the character models, settings, animation and FX hold up well enough to immerse instead of detract. There are some performance issues, such as enemies like an ogre or wolf pack clipping through the environment or otherwise glitching during confrontations. But such issues aren't surprising for a port of an older game that reportedly had its share. The fact that I've encountered similar problems in new releases shows this isn't exclusively an issue with past titles. In fact, the re-release of Risen, besides making the game accessible for a new generation of non-PC gamers, should highlight the game's timeless elements that are too often absent from modern releases. The game is not without its faults, but demonstrates clear advantages over formulaic titles that ignore the details. THQ Nordic and Piranha Bytes have done us a favor by reminding us of what makes a gaming experience that holds up over time. (This post was based on a review key of Risen for Nintendo Switch on January 24. The game also released on PlayStation 4 and Xbox One, and was updated on PC.) (Be sure to check out additional images here: Screenshots.) A Fisherman’s Tale was a revelation with its fairy tale story and creative puzzles that used perspective to great effect. It was relatively short but very immersive and certainly left a powerful impression. For these reasons I was excited to play Maskmaker, the latest game by A Fisherman’s Tale developer InnerspaceVR and publisher Vertigo Games. To be certain, there are welcome similarities that are apparent almost immediately. For one, art design is similarly stylistic and colorful. Maskmaker likewise opens almost like a fable or fairy tale, with a narrator introducing the story of a mask maker in search of an apprentice to carry on the trade. The player seems destined for the role. But something is clearly amiss as the player witnesses an argument behind a boarded up storefront before being led on a journey to uncover the fate of the mask maker and unravel the secret of what happened. It’s a solid foundation for what follows – a story of magic and mystery that takes the player to fantasy realms ruled by an enigmatic king. As the player and prospective apprentice, you are bestowed with the keys to the kingdom, figuratively and literally. The mask maker’s shop becomes a training ground for your nascent skills as you learn the trade and its significance, creating masks that, in turn, unlock the different realms you’ll visit on your quest to discover the truth. In this way, gameplay revolves around exploration, puzzle solving, collecting and mask making. Intuitive controls on the Meta Quest 2 mean actions are simple, quick and satisfying, whether carving a mask, painting it or accessories, wearing it, collecting items or interacting with other objects. Most actions are performed with the side grip buttons to hold and use various objects. I’m half to two-thirds of the way through the game, to judge by my mask collection and the realms visited, and no action thus far feels under- or over-utilized. I enjoy the process of mask making, including carving with chisel and mallet, adding accessories and painting, as well as puzzle-solving, which can involve using devices that incorporate winches, gears or other mechanisms. But where the game shines is in its puzzles that require the involvement of more than one character. A Fisherman’s Tale excelled at requiring players to interact with two versions of themselves to solve puzzles – a larger one outside a model replica of their world and another inside it. Maskmaker likewise uses different perspectives to overcome challenges. Donning masks not only sends players to new realms and different areas within them by inhabiting locals, but switching masks moves players back and forth between those individuals. That’s useful for gathering and sharing resources, and for operating devices remotely. Keeping these perspectives in mind helps elevate some of the puzzles. These core gameplay mechanics are supported by a useful hub in the form of the mask maker’s shop, where tools and accessories are in easy reach, including boards for respective masks and maps that suggest the materials to be found there. The diverse biomes themselves are easy to navigate and uncluttered, making resource collection easy, but include nice details and beautiful settings. It’s worth noting that comfort settings include snap turns and a vignette option, which make locomotion easy for me despite open areas having a corridor feel with lots of twisty pathways. The sense of scale is impressive as some locales are in high elevations like mountains or treetops and in that way reminiscent of Wayward Sky on PSVR. The inspired art design is not only supported by diverse ecosystems but also the structures, wardrobes and masks particular to each locale. Ambient sounds help immerse players, while narration and distinct, quality voice acting help provide context and propel the story, all supported by an unobtrusive but atmospheric score. I don’t want to delve too deep into the story as I’ve experienced it thus far, but it does raise issues and questions about the masks we all wear and the power of those identities. In that context, especially, it’s interesting to consider the act of inhabiting locals, i.e. others’ identities, in pursuit of your own goals. Besides the central mystery, I can only hope that this dilemma is addressed later on. I’ve spent hours in the game and already it’s a much larger experience than its 2-1/2 hour long predecessor, and the varied biomes and respective puzzles help keep gameplay fresh thus far. The mystery likewise provides incentive to push forward. Maskmaker has the ingredients to continue InnerspaceVR’s impressive success in the virtual reality space. The one caveat is that the puzzles thus far aren’t quite as inspired or challenging as those in A Fisherman’s Tale, though it would be hard for anyone to match the ingenuity of that experience. And it’s possible the puzzles could become more complex, as was the case with the other title. Still, the world building of Maskmaker, the care taken, and its use of masks do make for an entertaining journey. Maskmaker and A Fisherman’s Tale succeed at immersing players in their unique fantasy settings, which are just off the beaten path of our reality. The colorful worlds, evocative narration and engaging puzzles combine for a refreshing experience that bear the distinctive stamp of an original developer that likes to craft unique games that will keep this gamer coming back for more. (This post was based on a review key of Maskmaker for Meta Quest 2. The virtual reality game also released on Steam VR, PSVR, Oculus Rift and Viveport on December 15.) (Be sure to check out additional images here: Screenshots.) I enjoy many games, but it’s a rare gem that literally brings a smile to my face from the start. The Entropy Centre is such a title. The first time I used the object rewind gameplay mechanic to get to an otherwise inaccessible area I smiled from ear to ear. This clever element is used to great effect in this puzzle game, and hasn't become a tired gimmick during my playtime thanks to the assured design of indie developer Stubby Games.

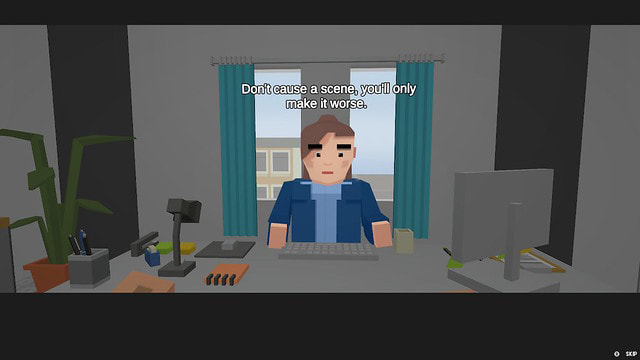

Players assume the role of Aria, a Junior Puzzle Operative at the titular facility. She awakens inside it to discover that the center is in an alarming state of disrepair, seemingly vacated and overgrown with foliage. Although the situation is dire, a Puzzle Exercise Assistant (PEA) named Astra (programmed into her Handheld Entropy Device or HED) shepherds her through her puzzle exercises. As it turns out, solving puzzles produces entropy, which the facility needs in order to operate. It’s an interesting conceit, as entropy otherwise can be described as “degeneration marked by increasing uncertainty, disorder, fragmentation, chaos, etc.; specifically, such a process regarded as the inevitable, terminal stage in the life of a social system or structure.” Astra does eventually explain how it works but even Aria scoffs at it. Their ongoing dialog not only provides context for the goings on, but also interjects humor into their predicament. If this setup reminds you of Portal, you’re not alone. The comparisons are understandable given the facility, the institutional AI seemingly in control, Aria’s situation and the projectile device and environmental puzzles that represent the kind of escape room gameplay that make up the journey. But the core mechanic of object rewind elevates this game not only to proud homage but a strong title in its own right with a creative twist on puzzle solving that requires a more thoughtful approach than standard challenges. Familiar pressure plates, crates and springboards make their appearance but time and limited resources are where the Handheld Entropy Device comes into play. Object rewind is the primary function of the tool, which allows the user to move objects in real time but also in reverse by about 30 seconds. When players are faced with multiple pressure plates and too few crates, for instance, placing them in the proper order for when time is ultimately rewound becomes the key to forward progress. If this hurts your head, well, it should. But in a good way. You basically have to solve each puzzle twice – once going forward to the exit, then again flowing backward to your start point in order to time object placement appropriately for the rewind. To the end. Trust me, it’s inspired and fun to figure out, especially when the game adds physical walls (breaking line of sight and object control), transformers (electrical fields that undo rewind) and multiple levels or sections to traverse in one area. To their credit, Stubby Games consistently introduces new features to keep the puzzles fresh while leaning into the rewind action. Besides doors, extendable bridges are activated with pressure plates. And jump, bridge and collapsible cubes are movable objects that enable players to select where they need traversal options. Combining these with the rewind function adds welcome layers to puzzle solving in levels that feature superior design. Speaking of level design, some areas have debris on the ground or are in a state of collapse. That debris can be rewound back to its original state, and will factor in to platforming options to maneuver through the area. The amount of options and ingenuity on display is impressive, and while I’d love to get into puzzle design I’m going to avoid giving away any more detail on that front to keep from spoiling the game, as the joy of discovery is part of what makes The Entropy Centre so fun. It’s worth noting that I'm playing the game on Steam Deck, and although it’s not a verified game as of this writing, the default Steam controls work well. Basic controls include left stick for movement, right for camera, Y to interact and B to jump/select. HED controls are Y to pickup objects, X to launch objects and R2 to rewind time (it also will charge electric panels). The game functions as a FPS, needing players to target objects close up to carry or any distance to rewind time. Players should know that their character CAN die, in my case when I found myself in the wrong place when rewinding debris or falling into water. Death sends you to the last checkpoint, which usually isn't too far back. Then there are the restarts that might be required, for instance, when I got stuck between objects or when a jump cube I was holding while jumping successively on another jump cube just disappeared and couldn’t be retrieved from a standing (replay) button in the puzzle chamber. Such instances have been rare and the game actually has few technical issues that I’ve encountered besides these and noticeable frame-rate drops upon entering new puzzle chambers, but they don’t impact gameplay outside of the occasional restart. Indeed, from a technical standpoint, The Entropy Centre is a quality title from its sterling gameplay to its challenging level design and quality production values that lend themselves to this failed high-tech facility. The setting, in fact, does a good job selling the game's premise -- from overgrown foliage to a facility seemingly abandoned in mid-operation, from the sounds of birds to running water and the noises of collapsing infrastructure or fracturing Earth. Our planet, as it turns out, is the figurative and literal backdrop for much of the goings-on. Astra and collectible emails reveal the emerging catastrophe while space-station views of Earth show its unfolding fate. The story thus far has provided a solid foundation for the puzzle-solving action, as entropy generated by puzzle solutions not only powers the station but factors into the Earth's fate. The game does a good job of doling out information while the score is at times subdued or suspenseful but always entertaining. At eight acts and multiple hours in, the puzzles keep me entertained without frustrating, the story remains compelling and the pacing has been good with new features regularly introduced. Initial comparisons to seminal puzzle game Portal are not misplaced but, to the credit of Stubby Games, The Entropy Centre boldly breaks new ground with its innovative object rewind feature. Solving some puzzles is incredibly satisfying when so many elements are at play. And the overall mystery complements the puzzle gameplay. It's a smartly conceived and executed game so far with hours of entertainment value that I can recommend for those seeking a clever puzzle challenge. (This post is based on a review key for the Steam version of The Entropy Centre, which released alongside other versions for PlayStation 4 & 5 and Xbox One & Series X/S on November 3.) (Be sure to check out additional images here: Screenshots.) Video games give you the freedom to do as you please, regardless of the moral implications. That freedom of choice is celebrated and encouraged as a means of player expression and wish fulfillment absent real life norms and responsibility. It's a rare game that not only attaches serious consequences to your actions, but forces those decisions on you as the main gameplay mechanic. Players who take on the role of Joe in Family Man will face moral choices every step of the way in the new indie title by Broken Bear Games (published by No More Robots). The life of the protagonist takes a seriously shocking turn at the beginning of the game, placing him in debt to the mob when he can least afford it. It's a solid premise and one that the game's design is structured to support throughout. To pay off the mob, Joe can perform jobs or tasks for the townspeople of Riverport. From flipping burgers at a local fast food joint to odd jobs including eradicating a rabbit problem, retrieving papers or running errands for local powerbrokers, players decide how Joe will make money. But legit options are limited, and payment is due to your crime bosses every day. This is where the drama comes in to play. Joe can also choose to perform criminal activities that pay better, however, engaging in them not only takes a personal toll but also degrades the town as criminal activity escalates. Add to that dilemma the challenge of looking after your own family -- their welfare, mental and emotional well-being, and household chores -- and cruel trade-offs proliferate. Neglect mob payoffs and Joe dies, neglect his own welfare and Joe dies, neglect his family and they leave Joe, neglect their welfare and they starve, etc. All are game-ending scenarios that exist every day over several weeks that Joe is expected to pay the mob. They lead to difficult decisions of time and resource management when not every obligation can be met. Broken Bear Games deserves credit for a clever premise that seems simple and relatively straightforward but is complex in execution. For instance, catering to your family's needs means satisfying different measures; but each action benefits some while detracting from others. That mirrors the overall gameplay where acts might help some townspeople at the expense of others. This leads to taut moments where players feel the weight of daily decisions amid the backdrop of a merciless day/night cycle. Few games are as effective at generating a sense of real consequence to one's actions or the related suspense of making the right choices within a limited window of opportunity. That the game succeeds at this for as long as it does is testament to the developer's efforts. I often felt pressed for time as I rushed to make enough money to pay off the mob each day while still allowing enough time to care for my family, including shopping for food or medicine, eradicating pests or washing dishes, playing games or making it home for bedtime. These competing obligations tear at the player but also at the game. It could be my poor decisions or execution, but the challenge of "doing it all" within a limited amount of time meant I was often sprinting everywhere, skipping dialogue and taking mob jobs first, and still enduring game-ending scenarios from time to time. For a game about choice, it felt sometimes like I had none. Though I'm sure others will have more success managing their obligations. It didn't help that the game ramps up difficulty in an artificial way that's similar to how stronger foes or more enemies greet players as they progress in adventure games. As players become more proficient at meeting their obligations each day, the mob would demand a bigger payment from Joe. It's not unrealistic given the game's premise, but did feel a little contrived. Because I relied on criminal activity to make ends meet, it meant an increase in the town's degradation. More thieves stood ready to intercept me, and I was at greater risk of wasting time in jail (I wasn't about to spend hard-earned cash to get out). Thankfully, players can upgrade abilities with earned points and obtain meat to feed their family by killing animals, both of which can improve survival. The problems with these is that the retrieved meat would often fall through the ground and the upgrades I chose didn't have much of an impact until about a third of the way through, when I'd earned enough points to unlock one in particular that made the game much easier. One upgrade shouldn't make that much difference but I'm grateful it did. One thing that surprised me about Family Man is that stealing food or money isn't an option despite criminal activity playing such a prominent role. There aren't even pickups off the thieves or other people you kill. Of course this all would undermine the chief gameplay mechanic but it's a notable incongruity in the game world that the developers created. That game world can suffer from other minor issues, such as a small map; overlapping, obscure or absent mission icons; too small prompts and menu text in handheld mode; interruptions by people, animals and phone (the latter causing a cheap death); and glitches that impede progress like irretrievable delivery packages, frozen inventory screens and an inaccessible home (forcing a restart of the day). Thankfully most are rare and don't often distract, which should allow players to better appreciate the game's appealing modular or block design of Riverport and its inhabitants (reminiscent in some ways to Minecraft), the comedic dialogue and discussion options between the player and colorful characters, or the melodic score that is (mostly) on point. If players can take the time to appreciate Joe's exchanges with townspeople, chances are the ending they receive will resonate more with them. Like the game's introductory shock, its ending can pack a wallop, if the one I unlocked (of several) is any indication. Crafting a solid premise that has such strong bookends is no small feat. In the end, Broken Bear Games is able to generate a suspenseful gameplay mechanic that makes every decision and action feel consequential in a way that too few games manage. But the intricacies of that design can sometimes weigh gameplay down or undermine choices. Still, it's a bold approach with a memorable start and finish (for me) that makes a visit to Riverport worth the trip. (This post is based on a review key for the Nintendo Switch version of Family Man, which released alongside Xbox Series X/S and Xbox One versions on September 14.) (Be sure to check out additional images here: Screenshots.) Player agency has often been at the center of gameplay design in a creative choice that seems conducive to an interactive medium. But that decision has resulted in formulaic approaches that often sacrifice story and character development. While the growth of independent studios has helped challenge that formula, games that resonate on an emotional or intellectual level are still the exception. State of Play's South of the Circle is one such title, as it forgoes the current obsession with action-adventure gameplay to craft a journey that is measured, thoughtful and more intimate than your average gaming saga. The game, published by 11 bit studios, is described as a narrative experience and cinematic story, and it succeeds on both those measures. But is it an unqualified success? South of the Circle follows the relationship between Peter Hamilton and Clara McKirrick as they navigate global, collegiate and gender politics during the turbulent 1960s and the tumult of the Cold War between the West and the Soviet Union. As junior lecturers among their Cambridge colleagues, they face pressure from friends, Peter's mentor Professor John Hargreaves, outside forces and past internal conflict. The pressures exerted on their relationship are mirrored by the threat presented by the global conflict between the superpowers. Both are existential crises that risk emotional devastation on the one hand and physical destruction on the other, and require those involved to weigh the consequences for themselves and others as they try to manage all the conflicting influences past and present. The narrative flows between present and past in ways that are organic and entertaining, using common elements like a road or bed to shift back and forth from 1964 Antarctica -- where the story begins -- to Cambridge to Peter's childhood (though Clara's youth also is addressed). In this way players learn of current dilemmas and past traumas while avoiding the confusion that can result from such transitions. The catalyst for such introspection is a fateful plane crash involving Peter and pilot Floyd, who was taking his passenger to a British base during a period of international tensions over the polar ice cap. The two are forced to find a way to survive, which triggers memories in Peter of his relationship with Clara, his time at Cambridge and the influence of his father. It helps that the dialogue is well written and the voice acting is excellent. Characters in turn are believably earnest, vulnerable, funny, caring, desperate, threatening and manipulative. Authentic portrayals of every character but especially Peter and Clara help immerse players in their relationships and the romance at the heart of the story, which makes the drama more effective and the consequences more profound. This effect is more pronounced and even startling considering that game design relies more on a stylistic, almost minimalist (but still stunning) presentation in mostly vibrant pastels instead of a realistic, detailed design including a broad color palette. That this world feels alive is also due in no small measure to excellent motion-capture animation, dramatic but subtle camera work and a beautiful score that enhances each scene without overwhelming. Supporting elements also come together to help create a believable world circa 1960s Antarctica and England. City, rural and natural settings are well designed, support cast like Clara's friend Molly and Peter's friends Sam and Joseph are well portrayed, and radio and paper reports add to the setting and story. All elements come together for an effective, involving and entertaining story about our choices, our influences and our resulting successes and mistakes. As successful as the game is in that regard, it still could disappoint some gamers if they expect the kind of gameplay associated with a more traditional action format. As a narrative experience and cinematic story, South of the Circle unwinds its plot to dramatic effect instead of relying on player agency and choice to entertain. There are controller inputs throughout the game, and while they help immerse players, they do little to impact what transpires on screen. A help menu shows dialogue symbols though I didn't access this until I questioned how the controls work. Each symbol has three reactions associated with it, i.e. panic, confusion and concern; forthright, strong and assertive; or enthusiastic interested and curious. It reminded me of Quantic Dream games where reactions emerge in the air and players choose one, affecting how the discussion unfolds. Only in this game, one selects a group. I effectively played through a couple times, choosing what I thought were opposite groups, and detected subtle changes in replies but no real impact on how dialogue or scenes played out. The same is true when presented with images as dialogue responses (i.e. suit, tie or shoes). And when one option is presented, there is no consequence to not selecting it (the comment just comes later). To be fair, State of Play has described the writing as nuanced, and this is an apt description for the dialogue options and their consequences, at least in my experience. Likewise, players can control Peter, whether walking, driving or interacting with items. But I didn't notice choices that deviate far from prescribed actions or a predetermined path. The overall impact is increased immersion, but within the constraints of the narrative. Of course, this isn't uncommon in many video game stories, but there is less latitude in South of the Circle given the very specific story being told. So if one approaches the game with that expectation, I think they'll enjoy the thoughtful, poignant and entertaining story much more. It's rare to find a well-executed narrative where the writing, acting and overall design makes for a compelling experience, and can be recommended on that level. I also can guarantee that the ending will make you think carefully about everything that transpired before -- about Peter's choices, about his relationships, even about memories of his childhood and more. Part of my second play-through was revisiting those things. It's a relatively short game at about four hours for me, but has an impact beyond that time. If you enjoy such contemplative stories, then check out South of the Circle. (This post is based on a review key for the Nintendo Switch version of South of the Circle, which releases alongside PlayStation 5, PlayStation 4, Xbox Series S/X, Xbox One and PC versions on August 3, 2022.) (Be sure to check out additional images here: Screenshots.) In a gaming landscape dominated by action games, it’s exciting to find titles that buck that trend in favor of more meditative and intriguing experiences where the journey is its own reward. Enter sci-fi adventure game Beautiful Desolation by developer The Brotherhood and publisher Untold Tales. Taking place in a fascinating post-apocalyptic South Africa, players will discover the world and uncover its mystery, and whether the creativity and attention to detail provide enough entertainment without relying on high-octane action. The setup for the player’s journey into this harrowing world is the aftermath of a brutal war when the auspicious arrival of an alien object named the Penrose heralds a period of technological advancement where disease and mortality are eradicated. But Heretics emerge against Penrose and its defender Penrose Allied, leading to a period of conflict. Into this setting comes skeptic Mark Leslie to investigate Penrose 10 years after its arrival and the resulting death of his fiance Charlize. Players control Mark as he enlists his older brother Don and they begin their pursuit of the truth. But before their investigation goes very far, an accident sends the two dramatically off-course and into an unfamiliar, far-off future where inhabitants worship or resist the highly advanced technologies that now rule their lives. How players interact with the wide variety of personalities they'll encounter will help determine the course of their journey and attempts to return to their own time. Indeed the game is described as a story-driven adventure game that forgoes RPG elements like character customization, loot grinding or constant combat in favor of exploration, consequential dialog options and some puzzles (in addition to mini-games and optional combat). From the start, players will navigate the world from an isometric perspective and converse with others in an indirect first-person perspective. The presentation in this regard is impressive, apparently owing to the photogrammetry that the South African developers used to put pieces of Africa into the levels, art and characters. Settings such as grasslands, marsh, shores or settlements are varied, detailed and colorful, creating interesting areas to explore on foot or from the air. During several hours I've explored three of the game's seven areas and am impressed with the natural and artificial landmarks, not to mention the ambient sounds present at each location. There is beauty to be found in Vesta, Zozo and Saxonwold, in the ruins, villages and places in between, not to mention in the imaginative characters that populate each locale. Organic and mechanical life comes in a wide variety of beings that exhibit equally varied beliefs, loyalties and personalities. There are sentient robots called agnates; servants of Dullahan, the creator of the world that they believe came from the Penrose; Witnesses of the Ascendency (which bestowed immortality), who provide gold and technology to the High Priests of Tribulation; and nonbelievers who reject Inja and followers the Kettle Maidens, to name but a few. Who they and others are, are better left to players to discover. Developer The Brotherhood reports that there are more than 40 unique characters, all of whom are voiced by African actors that speak thousands of lines of dialogue including multiple conversation paths. In fact, meeting and interacting with this world's characters is a high point of the game thanks to creative character design and strong voice acting that helps distinguish each individual and every encounter thus far. While I have yet to determine to what degree dialog choices affect the story, the conversations themselves are entertaining and worthwhile. These encounters do form the basis of the story, as characters will reveal details about this future that Mark and Don find themselves in, and suggest how the world changed since the arrival of the Penrose. As noted above, the post-apocalyptic free-for-all has resulted in a head-spinning menagerie of individuals and factions each with their own values and goals. It can be a challenge early on to keep it all straight, but it does make for an exceedingly colorful and eccentric cast that provide a lively journey even without regular combat. In these ways world-building feels like an accomplished feat, at least to judge by the first several hours. This is not insignificant considering that exploration and story play such a prominent role in Beautiful Desolation. But gameplay in general and the controls that enable it facilitate the player's journey, so do they likewise rise to the occasion? The developer touts that the game's controls, interface and movement have been revamped to provide an intuitive experience on consoles. On the Nintendo Switch, basic interface controls and menu work fine. The plus button opens the game menu for save, load, achievements and game/video/audio settings, which include accessibility options for text size, subtitles and color. The minus button toggles descriptions on/off in the isometric view, expanding on labels that identify objects in the environment (eye icons also highlight interactive points of interest, while notepads/pens identify noteworthy objects for the journal). L and R buttons control 6x magnification. The ZL button opens the inventory. Players select an item with X to Use With a point of interest, or with Y to combine it with another item. Uses can involve converting gold possessions to credits, which can then be used to purchase items from vendors; or combining items to gift in return for a favor. Items therefore have specific uses to obtain entry or objects that will help Mark and Don. This inventory system encourages progress, and is not your typical character-building, stats-buffing loot grind. An in-game handheld device is accessed via the ZR button. L and R buttons navigate between a network connection, map, recorded messages/dialog, Messages Review and To-Do List. The up direction key opens a journal/sketchbook, which includes clues (i.e. symbols, numbers). The down key opens a kind of walkie-talkie for contacting others or summoning the Buffalo transport. A is the action button for picking up items, initiating conversations, adding journal content and entering/exiting. All these work reasonably well. But problems arise (at least they did for me) when attempting to navigate in this world or track objectives. Character/transport movement is controlled by the left thumbstick and kept my character moving when on the correct path. The issue is that those paths are not always defined and when moving off the path, my character got stuck or movement impeded to the point that I had to struggle with the control stick to get back on the predetermined path. This issue is compounded when using the Buffalo transport to traverse the world from the air. Perhaps because of its relative speed, getting myself into sticky situations proved easy, though extricating myself out of them proved a challenge. Turning and forward movement felt less responsive with flight controls, and boundaries are even less clearly delineated with the aerial view. It's possible that my own skills are at fault, but I don't have this kind of trouble with other games. As for tracking objectives, I was left at a loss on several occasions. Maybe I'm spoiled by games that include a measure of handholding, but I did feel this element likewise was not that intuitive. Given the breadth of areas and objectives, I had to regularly consult not only with the To-Do List for tasks but also the recorded messages/dialog screen in some cases to remind myself where I needed to go to complete the task. I missed having related HUD indicators, quest logs to track progress, and related map icons for current tasks. All this lead to repeat menu visits, backtracking and fighting with controls just to stay on the correct path. Again, it could be partially my fault, but it's not something I struggle with in other titles. A little more clarity or clear boundaries would go a long way, especially for a game where exploration and story play such a prominent role in the experience and entertainment value of the game. It's worth noting, too, that the game did freeze when I chose to speak again at the Kettle door after initial conversation. On a promising note, The Brotherhood has indicated that dialog choices will impact the ending of the game, and that there are multiple ways to complete it. Side quests and world-building stories augment the experience, as do cutscenes that I have found well-designed overall. The instrumental/electronic music (by Mick Gordon) is upbeat and provides a good background score for the goings-on. Several hours into the game, and having explored three out of seven areas, I can say that Beautiful Desolation so far is overall a creative and intriguing experience that I'm eager to revisit. Meeting the bizarre but charismatic denizens of this future dystopia and learning about this world is a fascinating exercise from a player and world-building perspective. But like this cautionary tale there are technical issues that hold back the journey. I'm hopeful that the story and characters will continue to shine brightly, and be what players remember most about this odyssey. (This post is based on a review key for the Nintendo Switch version of Beautiful Desolation, which released alongside the PlayStation 4 version on May 28, 2021.) (Be sure to check out additional images here: Screenshots.) |

Author(SEE "ABOUT" PAGE FOR LINKS TO SPECIFIC ARTICLES.) Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed